Visit a traditional barbershop and you can get a haircut for under a tenner. It may not have the exoticism of today’s stylist or unisex salons, but its history is every bit as exotic, and much longer.

According to The Old Testament, in a tale of treachery and barbarism, Samson received one of the earliest recorded haircuts in 11th Century BC. Samson was one of the Nazarites of Israel who didn’t drink alcohol or cut their hair. All was well until he fell for a Philistine woman called Delilah and was going to marry her. Unfortunately, he rowed with her relations, who threatened her with death unless she discovered the secret of his awesome strength. He eventually gave the game away and told her it was his flowing locks and she had a servant barber carry out the No 1. all-over cut whilst Samson was asleep. His deep sleep cost him dearly, as the Philistines gouged his eyes out and chained him inside a temple. Their barbarity backfired when Samson’s hair grew and he, somewhat peevishly, pushed down the pillars of the temple, crushing many Philistines and himself to death.

The Barber’s trade crops up again when Alexander the Great gave it a boost in around 356 BC by insisting that all his soldiers be clean-shaven.

He saw this as a cunning tactic as, in hand-to-hand combat, his soldiers could seize their opponents by the beard with one hand, and stab them with the other!

It was the Romans who gave us the English word barber, which comes from the Latin for beard: barba. In ancient Rome, slaves were forced to wear beards to distinguish them from free men who were allowed to be clean shaven. This may also explain why the Romans referred to foreign tribes as Barbarian, as they were mostly beardies.

When the Roman legions finally left Britain in 410 AD the people of Britain were once again free to pick their own hairstyle. Consequently, there wasn’t much work for barbers for the next few hundred years, as the Anglo-Saxons favoured the ‘natural untouched look’.

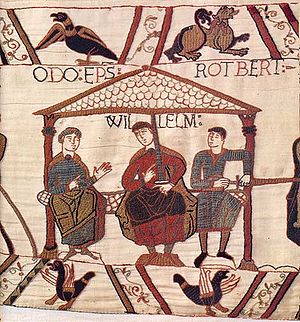

The arrival of the Normans in the 11th Century AD with their distinctive hairstyles might well have met with an enthusiastic welcome from unemployed barbers. With heads shaved at the back and hair combed forward at the front, there was no mistaking a Norman – Skinhead from behind, early Beatle from the front.

Throughout the Middle Ages most people couldn’t read, and shopkeepers used to have a sign or symbol outside their shop so that passers-by would know at a glance what was for sale. Barbers used a jaunty red and white striped pole to advertise their trade, examples of which can still be seen today in some towns and villages. But the barber’s pole signified a lot more than basic haircutting:

The barber’s predecessor was the barber-surgeon. As well as cutting hair and shaving beards, and in spite of no medical training, he also used to extract teeth, lance boils, set fractures, give enemas and practice phlebotomy. During this last bloodletting operation the unfortunate patient used to grip the pole, which was painted red to hide bloodstains; a bandage was wrapped around his arm, hence the pole’s white stripe. The barber-surgeon would then bleed him into a brass basin, which is represented by the gilt knob at the end of the pole. If, after all that, the customer still felt up to a shave, the same basin was used to hold shaving lather, presumably having first been rinsed out so it wouldn’t turn pink.

To distract waiting customers from the screams and wails of pain, musical instruments were often provided for them to play. It’s said that barbershops were popular informal gathering places for a bit of a chat or singsong, and are believed to be the forerunner to the ‘Barbershop’ style of music that was revived in the USA during the 19th Century, and which is still going strong today.

Before the days of doctors and paramedics, barber-surgeons used to accompany armies and travel on board war ships. As if war itself wasn’t bad enough, wounded soldiers and sailors had to rely on the dubious skills of barber-surgeons if they were to survive their injuries. As recently as the 16th Century even amputations were routinely carried out without anaesthetic, and gushing blood could only be stopped by sealing the wound with a red-hot iron or boiling oil (a process grandly termed cauterisation).

A French army barber-surgeon called Ambroise Paré was treating was treating wounded soldiers in 1545 when he ran out of cauterising oil. After many experiments, he came up with an alternative to cauterisation by mixing turpentine, eggs and rose oil together (as you do) and found that it sealed wounds without needing heat. It must have been an interesting experience for the wounded whilst he was still experimenting!

The Civil War in 17th Century Britain saw major conflict between the Puritans led by Thomas Cromwell and Royalists loyal to King Charles I. Barbers must have also been deeply divided between the shaven-headed Roundheads on one side and long haired Cavaliers on the other.

At the end of the Civil War, the defeated King Charles I received a rather closer shave than he had wished for, and short hair prevailed until 1660 when a new parliament invited his exiled son to return as King. Sharing both his father’s name and taste in coiffure, King Charles II also had long hair. Barbers hurriedly branched into supplying wigs to meet the surge in demand from men with cropped heads who wished to conceal their former allegiance.

Image courtesy of City of London, London Metropolitan

Archives

In 1745 the Company of Surgeons was set up in London, which went on to become the Royal College of Surgeons in 1800.

Barbers were excluded from membership and were constrained to providing hair products, shaving and weekend family planning accessories for their customers.

The Victorians, whilst having sensible haircuts, introduced a fashion that a journal of the day described as “an appendage of hair called a mustachio”; and long side-whiskers called “Piccadilly Weepers” or “Dundreary Whiskers”, which kept barbers busy.

The Twentieth Century saw most of the previous hairstyles coming back into fashion, sometimes simultaneously. Hair-care products, for men as well as women, turned into a multi-million pound industry, and technology improved to the extent that, if you so desired, you could have hair from one part of your body transplanted to another where it would continue to grow.

The number of high street shops has reduced dramatically as retailers have closed, merged, or been swallowed up by the big corporates. In spite of this seemingly inexorable change, barbershops in the Twenty-First Century have remained largely intact and unchanged. It may be that this is due to the friendly informal atmosphere that prevails inside. Or perhaps men still want that “something for the weekend”.

Discover more from Mark Braggins

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I wonder if the growing popularity of Movember will lead to more demand for moustache-related barbering. Over one hundred men at my husband’s work took part last year alone, and it looks set to become even bigger later this year – perhaps a revival of Dundreary Whiskers is on the cards 😉

I reckon you’ve got a point there. Movember has rapidly become quite an institution, and with the cyclical nature of fashion we may well see a return of Dundreary Whiskers before too long.